Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Still waiting for that ‘huge mea culpa’

Sept. 6, 2013

“The day-care trials couldn’t have happened without the active participation of social workers and therapists. Police authorities relied on the therapists to interpret what the child witnesses were saying, to interview the children and to counsel them about their alleged experiences. One might suppose that the realization that:

- People have been sent to prison for years for crimes that never happened;

- Children had been abused, not by the accused, but by misguided therapists who implanted false memories;

would have created a huge mea culpa among the professionals involved. This hasn’t happened.

“Some have defended their actions, if not the results, on the basis that their hearts were in the right place. Some have excused themselves on the basis that nobody knew any better – that, by golly, nobody could have guessed that rewarding children for making accusations, and questioning them until they did make accusations, might just lead to false accusations.

“And they speak, in self-pitying tones, about the ‘backlash’ – the (presumably) undeserved and irrational criticism that is flung their way.”

– From “The ‘Ritual Abuse’ Panic” at Imaginary Crimes

Mum’s still the word from the prosecution therapists in the Little Rascals case, except for Judy Abbott’s resentful response to the “backlash.”

Court finds Hart’s ploy ‘grossly improper’

March 16, 2012

“The appeals court called a maneuver (in Dawn Wilson’s trial) by the chief special prosecutor, Bill Hart, ‘grossly improper.’

“The judges found that Hart had tried to impugn the reputation of Wilson by placing in the courtroom audience two people whose presence was likely to intimidate Wilson.

“Hart never called the pair as witnesses, but… by his actions had implied to Wilson that he intended to use the two people against her in a way that might result in self-incrimination.”

– From the (Norfolk) Virginian-Pilot, May 3, 1995

In 1995 the N.C. Court of Appeals overturned her conviction. And then of course the prosecutors rushed to apologize to Dawn Wilson for their disgraceful vilification.

Fake news and ‘satanic ritual abuse’: Best friends forever!

vox.com

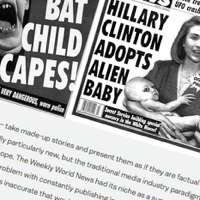

Covers from the Weekly World News.

Dec. 15, 2016

You probably haven’t been asking Google to provide you with daily news alerts about “satanic ritual abuse,” but if you had , the popularity of fake news would come as no surprise.

Decades of debunking may have squelched the wrongful prosecutions of day-care providers, but beneath the surface… well, these headlines sprang from just one day’s news feed:

-

Ritual Abuse is Real: Cover-up of Child Sexual and Ritual Abuse

-

Cover-up of the Century: Satanic Ritual Abuse and World Conspiracy

-

Ritual Abuse: What It Is, Why It Happens, And How To Help

-

Breaking the Circle of Satanic Ritual Abuse

-

Child Trafficking/Illuminati-Freemason Ritual Abuse

![]()

View from Edenton: Oh, the damage done….

March 1, 2021

I was surprised recently to notice a Facebook message from an elementary school teacher in Greenville, N.C.

Buddy Hyatt had grown up in Edenton and wanted to talk about the Little Rascals Day Care case. “It ripped apart many families and almost destroyed the town,” he wrote. “In 1989, when the accusations started, I was in first grade. But earlier I had attended Little Rascals. My parents had me and my younger brother checked over by an unbiased child psychiatrist in Greenville. After several sessions he reported that we had no indications of physical or sexual abuse.”

Buddy Hyatt

Buddy had multiple other windows on the case. ‘”My grandfather, Pete Manning, was editor and publisher of the Chowan Herald, and my dad was associate pastor and minister of music at Edenton Baptist.

“The Twiddys, the Kellys and Nancy Smith were all members of our church, as was [initial accuser] Jane Mabry Williams. This split the church right down the middle. Because the pastor and staff wouldn’t take sides, quite a few people got mad as fire. A good handful left. Some (especially those against the Kellys) spoke harshly and rudely to both my dad and grandmother.

“I feel most sorry for Bob and Betsy’s daughter, Laura. We had been in the same kindergarten class when the accusations started. My mom carpooled us. We did everything we could to be kind and remain friends with Laura and her family. I cannot imagine the pain and heartbreak they experienced.

“Lew, I know that’s a lot of information. Forgive me. I am happy to talk any time about the case or Little Rascals. The accusations and trial were a travesty and left so many people hurt and broken. No matter how much exoneration is given, the damage is already done.”

A few days passed before I heard from Buddy again: “Forgive me for being slow to respond. I happened to catch Covid, so the past week has been quite a struggle. Once I get through this (hopefully I’m on the tail end of it), we can plan to talk….”

Two weeks later Buddy Hyatt was dead. We never talked. I’m grateful for his big-hearted recollections and for his resolve to say more. RIP, Buddy.

![]()

0 CommentsComment on Facebook